- Home

- Alyssa Mastromonaco

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? Page 3

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? Read online

Page 3

The tour was 3,500 miles across 20 states and something like 52 cities in 17 days; it involved buses, trains, and boats. Having never done anything like this, or heard of anyone doing anything like this, I didn’t know if my apprehension toward the plan was just me being afraid I would fail or if it was actually ludicrous. Parts of the tour were based on something Al Gore did in 2000, but it wasn’t this extreme. I had misgivings from the start—if only for the fact that on campaigns you want ultimate flexibility, and the minute the train left the station (literally and figuratively), we lost that completely. But you don’t want to be the “can’t” person. Especially when everyone having a sense of optimism is really important.

I thought it wouldn’t work, but I didn’t know it wouldn’t work, so I didn’t say anything. That might be the difference between men and women: Women need to know they are right before they stand up. Men are OK objecting if they just think they might be right. I thought, but I didn’t know.

The tour was, in fact, too much. We executed it, but barely, and it broke almost everyone involved. Tears, night terrors, panic attacks—you name it. Everything was harder than we expected. Two families, little kids, elected officials, time zones. The most important thing I had wanted to do was let each scheduler leave the night before their segment started in order to meet up with the traveling staff to experience what they had planned; in most cases, I had to tell them to stay behind because there was too much work to do.

From the outside, we looked smooth; the events were beautiful, we executed what we needed to execute, and the bus never broke down. But everything was constantly a photo finish, and senior campaign staff never seemed to acknowledge the stress that put on us. It was partially because there were so many senior people without clearly defined roles, and everyone else had a hard time distinguishing whose word was the final one. There were a lot of endless email chains.

One particularly awful moment was when we were trying to cut costs right before a fund-raiser in New York. At the beginning of the campaign, people had shared hotel rooms, but as the race wore on and people got fewer breaks, we started letting people have their own. Before this New York trip, every hotel was sold out; the only place we could stay was the Mandarin Oriental on Central Park. I told everyone they would be sharing rooms.

A few hours later, a young traveling assistant called me up, apparently just because she wanted to practice being passive-aggressive in a professional setting. “I heard we’re sharing rooms at the Mandarin,” she said. “I just wanted to know who approved that.”

“I approved it. Do you want me to get confirmation from Mary Beth?”

She did. OK. I went to Mary Beth—whom I liked very much—and told her we were getting pushback about making people share rooms. (If “pushback” sounds like one of those office code words you use to say something without really saying it—that’s because it is.) Mary Beth replied that people should always be sharing rooms.

I thought that was the end of it until some guy called me from the tarmac as he was about to board his flight to New York. “Are you fucking stupid?” he yelled into the phone. He said I reported to him, not to Mary Beth, even though I reported to Mary Beth; he was mad that I had basically outed him for spending too much money on individual hotel rooms. “Did you fucking lose your mind?”

Today, I would tell that guy to go fuck himself. But back then I was so sleep deprived, and so fed up with having no idea who was in charge, it made me cry.

By the time the Kerry and Edwards families got to Missouri—less than halfway through the Believe in America’s Sea to Shining Sea tour—they were exhausted. We stopped the whole production for a day so they would not have to be physically moving, but even that was not real rest: Since we then had to push every stop back by 24 hours, we almost couldn’t find hotel rooms at the last minute because the Little League World Series was in one of the towns we had planned to spend the night in. I think we ended up finding space in one of the hotels where a losing team had been staying and left early—maybe this can be some solace to them.

After the tour, I think the campaign lost some confidence in my abilities, because they brought in a “senior adviser” to oversee the scheduling and advance departments. His first move was to take my desk. We nicknamed him Bela Karolyi, after the Romanian gymnastics coach, because we felt that he treated us like little gymnasts walking to the mat for comments; he would call down the other schedulers one by one to go over their work with them. Sometimes, when he wasn’t looking, we would do a little dismount pose.

I wanted to sulk, but there was so much to do that I didn’t have time. I decided not to ask what he wanted my role to be and just kept doing what I had been doing. While I was hurt that they brought in someone to oversee my department, I was also 28 and had never worked on a presidential campaign before. Once he started, I think he realized that the mess of personalities I was dealing with wasn’t easy. The senior team realized it eventually, too; the problems they thought the senior adviser would come in and fix persisted, because people kept making decisions too late and changing their minds at the last minute.

Campaigns always take a physical toll on you as well, but this was something else. Tey and I lived right down the street from each other on Capitol Hill, and she had a super fun Mazda Miata convertible that she would drive me home in. One day, we walked into the garage, and she realized she had left her car running for the entire workday—she was so tired when she came into work that she had just put it in park and gotten out.

A few days later, I woke up with a mouth full of blood. It hurt, a lot, but I was also very confused. After a few minutes of horrified, painful examination in the bathroom mirror, I deduced I had shattered a wisdom tooth grinding in my sleep, and the sharp edge had cut my tongue. I took Advil for a few days until I gave up and accepted that I really did have to go to a dentist.

When I went in for my appointment, he quickly assessed that I needed all four of my wisdom teeth out immediately. That day. I said OK. He gave me a muscle relaxer and some Advil and then knocked me out. I couldn’t take any time off in the middle of the campaign, so I worked from home with frozen peas on my cheeks for two days, biting down on green tea bags soaked in cold water to avoid dry socket. The peas were one of the best parts; this was late August, and it was so hot in my apartment. Besides that I just ate mushed bananas and slurred.

I wish I could say this came out of nowhere—that even at 28 I was a responsible angel who never took any risks when it came to her health—but I had experienced intense pain for weeks before my tooth broke, and I just ignored it. I knew Tey had been doing the same, so I made her go see the dentist, too. She also needed her wisdom teeth out. We were a mess.

When election night rolled around, we went off to Boston as a team. I put on my “election night” pants (read: non-yoga pants) and immediately split them with my fat campaign ass, so I had to put on my fat Gap skirt. When we all met downstairs in the hotel bar, exit polls were saying we were killing it—Kerry was up. After all that, it was such a relief. We celebrated. We drank.

And drank. And drank. As we were enjoying what was probably our one real moment of merriment, the tide turned. Ohio was looking terrible. CNN was on a TV over the bar, and it was getting weird and panicky. We all agreed we needed to go upstairs and get ourselves fresh—just in case.

Unfortunately, we were hammered. Someone puked in her purse in the elevator. Within hours of our drinking binge we were back on our computers and on a conference call, planning John Kerry’s concession speech at Faneuil Hall. I guess we were lucky the space happened to be available, because I don’t know where else he could have given it. But we didn’t feel lucky.

The next morning in Boston was really pretty, crisp and autumnal, the way you imagine Boston, and I was trying not to cry the whole time. We all sat in a row together and listened to reporters saying really shitty things: “They ran the worst campaign”; “If John Kerry weren’t so aloof, maybe he would have had a chance”; �

�I mean, they had SO many slogans.” It was going to be four more years of George Bush. Someone from the campaign eventually turned around and told them to shut the fuck up.

When I got home to DC from Boston, I found that someone had hit my Saab, which was parked outside my apartment. She left a note with her phone number. Very nice. I called her and got a voice mail that said, “Hi! If you’re getting this message, it’s because I’m out celebrating four more years of George Bush! Leave me a message.”

I hung up. I didn’t need a new headlight that badly.

Four years later, I sat at my desk in Chicago counting down the hours to election night and reflecting on what had been a very different campaign (except for the “bitch” comment, which I survived). Our event was going to be outside in Grant Park, and the weather was freakishly good for November—75 and sunny. I fidgeted with the stuff on my desk. I checked my email. I made some lists. I was worried that it would rain during Obama’s future acceptance/concession speech, and I felt like if I had a raincoat it wouldn’t rain, but then I felt like it would be stupid to go and buy a raincoat in the middle of Election Day in order to ensure your candidate wins. Eventually I gave in to superstition and walked to North Face.

When I came back to the office, the whole team was gone.

I got so mad. What could they be doing? Resting on their laurels? Day drinking? How many times did I have to tell them the purse-puking story? (It WAS NOT me, I swear.) I became angrier and angrier—not that they were out, because there was nothing to do but wait, but that they were jinxing everything. In reality, they were gone for only about an hour, but if you’re sitting at your desk “not looking at” exit polls, any length of time feels like eternity, and it was only 1:00 PM.

When they all came back, I was prepared to give them some really biting commentary—but then they gave me a gift: this really funny picture of me and Obama sitting on a street corner in South Carolina, with a handwritten note from him, all in a frame.

By the time evening rolled around, people had started to get on the trolleys we rented to take supporters and staff down to Grant Park—Lake Shore Drive was closed to traffic, and this was our festive idea for transportation. I kept telling the team I would catch up with them later; I thought I was going to pass out from nerves. I was the last person on my floor. Finally, Dey and my good friend Jessica Wright—Jess was also on my team—came up to me and made me leave; they weren’t going to let me sit there by myself as the votes came in. It was also pretty clear that I alone could not sink the ship, regardless of what had happened four years before.

We put on the wristbands to get into Grant Park and went down to Houlihan’s to pregame with some Pinot Grigio and buffalo chicken baskets. We were down to a few tenders when New Mexico was called and then, I think, Ohio. At one point, we all looked at one another and just said, “Oh my God!”

We paid our bill, ran over to the Hyatt, and got one of the last trolleys to Grant Park. Lake Shore Drive was quiet, but as we got closer we could hear people cheering and screaming. Our trolley pulled up to the VIP entrance, and we jumped off and ran as fast as we could. There he was, good old Wolf Blitzer, saying, “CNN can now predict Barack Obama will be the forty-fourth president of the United States.” We got there just in time to see the reaction.

The scene was surreal. Reverend Jesse Jackson was trying to lift Oprah up so she could either see better or get over a fence. Brad Pitt was standing next to us and crying.

I stayed for a little while to celebrate, but I was home by midnight. I had to be ready for the next day.

I had relocated to Chicago for the campaign, and I lived in River North, a neighborhood not that far away from Grant Park. When I first got there, it was silent—totally surreal. I got ready for bed feeling crazy—elated yet tearful, exhausted yet wired. It was still warm out, so I opened the windows. As I set my alarm for 5:30 AM, I could hear kids coming down the street chanting, “Yes we can!”

I learned a lot about leadership from Obama. (Obviously.) As a boss, he isn’t someone who makes you feel like you have to prove yourself; there’s no external pressure to make you procrastinate or take shortcuts. He never yelled or demeaned people—even if you let him down, he would move on if you admitted it up front. He assumed we were all adults and learned our own lessons.

As a president, he could be a bit more aggressive if the occasion called for it. In December 2009, we went to the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. In the days and weeks leading up to the summit, we didn’t know if POTUS would need to be there; progress on negotiations was slow, and it wasn’t clear if the negotiators would be ready for heads of state to get involved.

About a week before the convention, we decided to make the trip, but on a totally crazy schedule: POTUS would get off the plane at about 7:00 AM, head over to the convention center immediately, and get out of there when negotiations were over without even staying overnight. The summit was very close to Christmas, and we didn’t want to get stuck in Denmark if the weather was bad.

When we got to the convention center, the vibe was off—chaotic and tense. For one thing, they also hold the Copenhagen International Fashion Fair at the same location, and the waiting room where they kept the US delegation contained what I can only describe as an abandoned denim bar: There were a bunch of naked mannequins. For another, negotiations were not going well. Four newly industrialized countries—Brazil, South Africa, India, and China (BASIC)—formed an alliance just before the conference and committed to acting as a bloc in order to protect themselves against what they viewed as limiting measures from developed nations. It was sort of up to POTUS and the Chinese premier, Wen Jiabao, to bring everyone together on some kind of compromise.

But people were acting really weird. POTUS had requested to meet with Premier Wen, as well as with the Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva; the Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh; and the South African president, Jacob Zuma. By the afternoon, we started getting reports that the Indian delegation had left—like, gone to the airport. The whole thing threatened to unravel. The Brazilians said they didn’t know if President da Silva should meet with POTUS without the Indian delegation; the South Africans said Zuma wouldn’t do it without the others, either. No one knew where any of the leaders were—except for Singh, who had apparently gone home.

Suddenly, Secretary Hillary Clinton, who was heading up the negotiations with POTUS, came over to me. “Alyssa, can you confirm the Indians are at the airport?”

We sent our advance team to survey the convention center and figure out what the hell was going on. Soon, we heard that the Indian delegation were not on their way home but at a “secret” meeting called by Premier Wen. One by one, emails came in: All the missing delegations were in the same room. They wanted to avoid negotiating with us.

POTUS and Secretary Clinton didn’t waste any time. They rallied a few key players and headed to the conference room where the meeting was supposedly taking place.

They arrived outside the room to find a bunch of shocked Chinese officials who tried to send them in the other direction. Gibbs got into an argument with a Chinese security agent; in the meantime, POTUS waltzed through the door and exclaimed, grinning, “Premier Wen! Are you ready for me?” Secretary Clinton wrote in her memoir that she “ducked under” the Chinese guards’ arms to make it inside.

Everyone was totally flabbergasted—but then, thanks to the leadership POTUS and Secretary Clinton displayed, they were able to hammer something out.

But that was not the end of it. As the negotiations stretched longer and longer, I sat in the denim bar with the rest of the delegation and began to get reports that the weather in DC was not looking good. A snowstorm was closing in on the city, and if we didn’t leave soon—like, right then, according to the military aides—they would close Andrews Air Force Base before we could touch down. The military aides began to pressure me to pull POTUS out of his meeting so we could make it home.

Even though pretty much ev

eryone disagreed with me, I made them wait. (There also wasn’t much food around, though General Jones, a national security adviser, eventually showed up with a case of wine.) The situation had been so tense—and the stakes were so high—that I knew we had to give POTUS as much time as he needed.

The meeting ended up lasting about an hour and a half, and we took off out of Copenhagen two and a half minutes before we would have been held there because of weather. Although it was the roughest landing we ever made in Air Force One, POTUS got an agreement out of that meeting. Persistence will get you far, and leaders have to champion the push.

After Obama won the election in 2008, I kept my job, as director of scheduling and advance, for the president, until I was promoted to deputy chief of staff for operations in January 2011. I got the promotion because Jim Messina decided to leave his position as deputy chief of staff to be the campaign manager for the 2012 reelection, and in a matter of hours I had been offered the job and accepted it. It was a “reach” job—not a lateral move—but there was no question about whether I wanted to do it.

I had very little time to prepare my questions for Jim, and even less time to spend with him and ask them. I got about 15 minutes to interview him and figure out how I was going to do this. “This” being: oversee all the goings-on of the White House campus; serve as the acting chief of staff for the president whenever he traveled; manage presidential events and the hiring process for the executive branch; screen nominees for Cabinet positions; and coordinate among the Secret Service, the first family, and the White House Military Office (WHMO), including Air Force One and Marine One.

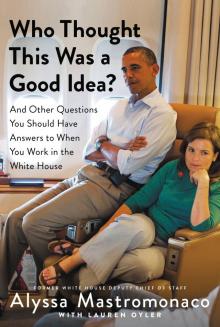

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?