- Home

- Alyssa Mastromonaco

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? Page 2

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? Read online

Page 2

Dey and I got dropped off outside Caribou Coffee and shuffled our way down Pennsylvania Avenue, both regretting the past three months; breakfast bagel sandwiches with extra meat had become the rule, not the exception. I was scared shitless. Between my physical discomfort and my anxiety, I was sort of a wreck.

We got to the gate by the Eisenhower Executive Office Building and presented our IDs, and the agent told us our meeting that day would not be in that building—instead, it would be in the West Wing. We tried to convince the guard he was wrong, but he wasn’t. After we went through our security screening—eagerly handing over our IDs again and waddling through the magnetometers—we held hands all the way down the walkway, past Pebble Beach where the reporters do their stand-ups, and into West Reception. Marines opened the doors for us. We looked around and wondered if they thought we were someone else, but then we just kept walking. (Another good piece of advice is to look like you belong.)

West Reception is hard to process—it’s like if the waiting room for your office were a museum. Heads of state, diplomats, celebrities, and activists all walk through it on their way to meetings in the West Wing or with the president. It was a week or so before Christmas, and all the holiday decorations were up. We chatted about the wreaths and the trees and the ornaments—they are always very beautiful—while we waited to see Josh Bolten, President Bush’s chief of staff, who wanted to welcome us and see if we had any questions for him. Besides, like, “What now?”

After our meeting ended, Melissa Bennett, President Bush’s director of scheduling, took us to the Oval Office. The door was open, but we were so nervous that we just stood at the threshold. We were being such tools, but we knew no other way to be. Finally, they coaxed us in.

The Oval Office was much brighter than on The West Wing, which was off-putting for a second; it almost looks more like a TV set than what you see on TV. (I would later learn that they keep it that way so reporters don’t have to bring lights to shoot there.) The wallpaper is the best wallpaper you have ever seen; the artwork would be in a museum if it weren’t in the White House; the desk is the president’s desk. Yet everyone was so happy and friendly and kind to us. At some point, I realized I wasn’t watching a TV show—this was going to be my life.

CHAPTER 1

Leadership, or Born to Run Things

The bathroom situation in the West Wing is probably not what you would expect: Toilets do not exactly abound. For women, there was only one full restroom on the ground floor, plus a single toilet in the hall on the main floor and one on the third floor. You would often find yourself waiting in line. What’s more, the bathroom you were waiting in line for was not some elegantly decorated powder room with a gilded mirror and a pink fainting sofa and fancy soaps and lotions selected by Nancy Reagan and Jackie Kennedy. Besides a little primping antechamber with a countertop and a mirror, it was your standard office bathroom—three stalls, some sinks, unflattering light, and that’s it.

On top of this, there were no tampons. I didn’t think this was a big deal when I started working in the West Wing in 2009, but it was a huge pain to get out of the White House once you were already on the grounds—there was no running across the street to CVS between meetings. To leave, you had to brave the lines of tourists stopping in the middle of the sidewalk to take photos, and to come back, you had to show your ID, input your special code, put your bag through the security scanner, go through the metal detector. Everyone was always too busy to go through this in the middle of the day. (This is also why we always ate at the Navy Mess, the cafeteria across from the Situation Room where the Navy serves breakfast and lunch every day.) If it was a true emergency, I would sometimes ask my assistant, Clay Dumas, to run to CVS, but I started doing it so often that I began to feel guilty about it. He was busy, too.

The White House was also not a scene where you could just bum a tampon from your girlfriends. Though this is changing, there are not a ton of women working in the West Wing, and many of those who are there have already gone through menopause—not many people traveled with a stash of Tampax. Those of us who did still get our periods developed an understanding with one another, and with our assistants, that it was cool to go through someone else’s bag or drawer in search of a feminine hygiene product while she was out. Still, it was not uncommon to find yourself in a… code red.

To support one another through the gender imbalance in the West Wing, some of the senior staff women and Cabinet secretaries organized regular dinners where about 15 of us would get together, talk about issues, and drink some wine. Perhaps appropriately, I got my period on the day of one of these dinners.

That workday was extremely busy, and I exhausted my tampon supply with no chance to replenish. As the time to leave for dinner approached, I began to do some calculations in my head. They weren’t good. I needed to change my tampon, soon. Before I left.

I began to panic. Neither Danielle nor any of the girls downstairs had anything that could help me. The toilet paper in the bathroom was not absorbent, so you couldn’t do the thing where you roll it around your underwear to make a diaper. I decided I would have to run to CVS before the dinner started.

No luck. A meeting ran long, POTUS had a question I had to find the answer to—I don’t know what happened, but I ran out of time. I hopped in my car and barely made it to the dinner—I was one of the younger women going, so I didn’t want to be late.

I thought everything was going to be OK, but I was wrong. In the middle of the dinner, someone said something funny, and as I began to laugh, my hearty “Ha!” quickly turned to, “Oh my God, oh my God, no no no.” It was then that I began to bleed through my pants—coincidentally, also my favorite pair at the time. Blue-and-white houndstooth capris from J.Crew.

Of all the women at the table, probably about four of us still got our periods, and I knew the others didn’t have tampons because I’d already asked them. I decided to abandon my dinner. I leaned over to my friend Kathy Ruemmler (who was White House counsel) and told her what was happening. She escorted me out to my car, where I bled on the front seat as I made my getaway.

The next day, I made it my mission to get a tampon dispenser in the West Wing women’s bathroom. If we were truly serious about running a diverse operation and bringing more women into politics, we should give the office a basic level of comfort for them. Even if you had to pay a quarter, it would be better than menstruating all over the Oval.

There was no objection to my proposal; it just seemed like no one had thought of it before. I went to the head of the office of management and administration, Katy Kale, and said, “Hey, we should put a tampon dispenser in the women’s bathroom,” and she said OK.

A couple of weeks later, I walked into the 8:30 AM senior staff meeting—populated by about 20 or 25 people, including a lot of men—in the Roosevelt Room. The Roosevelt Room is a stately conference space where FDR once kept an aquarium and several mounted fish; today, it’s decorated in subtle beiges, with a painting of Teddy on a horse in Rough Riders gear and a little statue of a buffalo. It was there that I announced the West Wing would be installing a tampon dispenser in the women’s restroom that day. No one said a word, but it felt really good.

I realize I promised you that I didn’t want to focus on “my legacy” in this book, but since they didn’t engrave the tampon dispenser with “Made possible by Alyssa Mastromonaco,” I wanted to leave a record of it somewhere. There are times when you need to be a bull in a china shop to get something done, and I’m capable of that, but I usually don’t enjoy it. For me, leadership has always been much more about rallying people around a project or cause than about being held up as the Boss.

But leadership is not all triumph and victory; if your ideas don’t work out, being a strong leader can carry you through to better times. My first formative experience with being in charge was when I was elected junior class president in high school. Even with my nuanced, enlightened approach, I was not popular. I ran for the position because I want

ed to take the lead on prom planning for our senior year. (Turns out you actually only needed to be on prom committee for that, but oh well.) We ended up using the song my best friend, Cara, and I wanted, “All I Want Is You” by U2, for our special prom anthem. (I don’t know why you need one, but you do.) Our theme was Riches in the Night, which is a line from “All I Want Is You,” so we thought we were extremely provocative and edgy.

It almost didn’t happen. After I was elected, a rival classmate decided that my junior prom date, who had a white Bronco with an eight ball tinted into the back window, was inappropriate.

The eight ball implied—but did not necessarily confirm, given how much high school boys love bragging—that he was a drug dealer, and my rival launched an impeachment campaign against me weeks before the dance. The betrayal culminated in my class adviser interviewing me about why I was a good and worthy class president in the gym in front of all my classmates, who were sitting on the bleachers.

I was furious, but I had to push forward. Senior prom could not be lame!

The people voted, and I remained; one of the hallmarks of a great leader is being able to explain your decisions. When I was in college and Bill Clinton was going through his impeachment proceedings, I remember thinking that not everyone could speak with the same elegance and finesse that I had displayed during Eight-Ball Gate.

Senior year, I ran for band president. Not because I wanted the glory of being band president—though it was a very high-profile position—but because I wanted our senior band trip to be to New Orleans. My platform was solid; all the members of the band agreed that we should go to the competition in NOLA. But we ended up in Philadelphia. Maybe sometimes rallying support for your ideas isn’t enough; maybe taking 40 teenagers to Bourbon Street will always be a hard sell to the principal. After I left, selection of the band president became an appointed position, no longer voted upon.

When I graduated from college, I got a job as a paralegal for the law firm Thacher Proffitt & Wood, which was located in the World Trade Center. Initially, I was not into this; I had wanted a job on Capitol Hill, but none of the (many) places I applied hired me, so I went to a headhunter in New York City who got me an interview with TPW. (And many other law firms, but none of them called me back.) I was disappointed, but I came around. It would be exciting to work in such a famous building—I liked the hustle-and-bustle vibe immediately. Also, TPW was the only firm that didn’t ask for my GPA. My grades were fine—I had a three-point-something—but at the other firms it was like you had to be Phi Beta Kappa to Xerox closing documents.

We sat in a room we called the Para Pit, and each of us worked for one partner and two or three associates. I worked for Ellen Goodwin, the only female partner, and two other lawyers. One, David Hall, took me under his wing and taught me a lot about real estate investment trusts, which still comes in handy during Jeopardy! or when I’m trying to convince real estate agents that they shouldn’t take me for a fool.

The company had a big deal in the works—a 30-plus property cross-collateralized loan involving more than 20 states—and I was the paralegal assigned to it. By this point, my coworker Amy Volpe (rechristened “Volpes”) and I were sleeping side by side in twin beds in a one-bedroom apartment in SoHo, and she would tease me about being the “Super Para” because I would talk about the deal all the time. I worked on it for months, and I got some decent attention from the lawyers about my work, but she wasn’t wrong—I was so pumped that I had been given so much responsibility that it fully went to my head.

There were hundreds of documents that would need to be signed at the closing—or the sealing of the deal—and they all had multiple signatories, including notary publics. Every signatory had his or her own color—green, yellow, red, orange, blue—and because I was very thorough, I made sure to tag them all the same way so everyone could see a sea of rainbow tags when they walked into the room. This was important, because very shortly there would be about 10 people representing millions of dollars in there, and they would want to close this out fast. Each signatory was assigned a color—e.g., Chase Manhattan was green—so they could flip to their signature page, get it over with, and move on to their celebratory steak and champagne.

As the closing approached, the office started getting chaotic. Documents were being swapped out, signature pages were changing, and I was only one person monitoring it all. I was staying very late and stuffing my face with free dumplings every night. The only good thing about it was that I occasionally got to come in later, and one morning John F. Kennedy Jr. asked to borrow my newspaper while I was drinking coffee at a place in Tribeca. It was the best coffee of my life.

A real leader would have delegated and enlisted help, but few 22-year-olds are real leaders. I didn’t want to share the credit with anyone else. I thought that since I had come this far and done so much work, I just needed to get it together and get it done.

On the day of the closing, it caught up with me. As all the signatories, representing tens of millions of dollars, were assembling to start signing, the notary and one of the junior partners realized something was wrong: I hadn’t double-checked with the attorney on the required margin sizes (the margins of a document matter in some states). The Washington State documents were wrong. Basically useless. Couldn’t be signed.

When clients pay you a bunch of money to represent them in a deal, and on the very day it’s supposed to close some aspects of the closing resemble a shitshow—well, that doesn’t inspire confidence. David Hall, who was effectively my boss, came up to me and very discreetly said, “Mende [that’s my middle name], you are the only person who knows what is going on in this room right now, and that is scaring the shit out of me.” None of the clients knew I had fucked up—and I needed to keep it that way.

I covertly grabbed all the messed-up documents and brought them to the Para Pit, in full crisis mode. We had to replace, retag, and remargin, fast. It sounds melodramatic, and it is, but at the time I was flipping out.

The other paralegals sprang into action; everyone took a set of documents and got to work. Papers were flying everywhere. I think we fixed everything within half an hour, and no one in the room—other than the notary and David Hall—knew there had been such a near disaster. Even though this was obvious before, I hadn’t realized until that moment that being called the Super Para was basically the equivalent of being called a douche.

It was a few years later when I got a taste of how I could actually succeed as a leader. I eventually got a job in politics, with Senator John Kerry, and worked my way up to become the deputy scheduler on his 2004 presidential campaign. This meant that I came in every day, sat at my desk, talked to all the advance teams out on the road, and worked with my boss and the senior campaign staff to plan trips.

On a campaign, there is no more important commodity than the candidate’s time, and when you’re part of the scheduling and advance team (SkedAdv), that’s what you control. This often leads to receiving a lot of enraged emails from state offices basically accusing you of ruining their chances of winning a primary or caucus because you’re a dumb fuck who doesn’t understand what you’re doing. For example: During the Obama campaign, the South Carolina office called up this senior adviser on our team to complain about me because I wouldn’t give them what they wanted; the adviser relayed their comments to me by saying, “You need to be careful before people start thinking you’re a bitch.”

What you realize is that everyone has her own priorities—her own constituency. Often, being a leader is not about making grand proclamations or telling people what to do; it’s about balancing all these priorities and constituencies. The finance team wants time for fund-raisers. The political team wants to get meet and greets for their politicians. The press shop wants time for interviews and to make sure that the best event of the day is hitting live for the local news (this is less important in 2016 than it was in 2004, but there are still times that are better for traffic than others). The candidate wants time to sl

eep so they don’t get too exhausted and say dumb shit. I was the arbiter of these decisions.

In the spring of 2004, my boss—the director of scheduling—got the opportunity to go back to school. I was worried about who they would hire to replace her. She was tough, but we had a very good relationship, which wasn’t necessarily true with everyone on that campaign. When Mary Beth Cahill, the campaign manager, called me to her office, I prepared myself for the news. I never thought that she would offer the job to me.

But she did. I was 28.

I worked with Terry Krinvic (Tey), who had been scheduling longer and on more campaigns than I had, and it felt weird that I was her boss. But I had been around the Kerry crew longer, which counted for something, and Tey was cool about it. Jessica Wright was our very smart assistant; she had just graduated from Wellesley, and we had her doing things like calling restaurants in the cities Kerry was going to be in so that we could get copies of their menus to order dinner for him and the team to take on the bus or plane. Glamorous and fulfilling.

As we drifted into late spring, we hired a few more schedulers, but late June bit us in the ass—we were getting ready to choose a vice president, and the convention was coming up. We had decided to do a swing into the convention—a thematic, multiday trip that would hit on key points of Kerry’s biography—and then go on a tour called both Sea to Shining Sea and Believe in America, which would leave Boston the day after the senator accepted the nomination. The Kerry campaign was notorious for having too many slogans—approximately 13 by Election Day—because we could never pick just one. My favorite was “The Real Deal,” which we put on a bus in Iowa that we called the Real Deal Express; there was also “A stronger America begins at home,” “A safer, stronger, more secure America,” “The courage to do what’s right for America,” “Together, we can build a stronger America,” “A lifetime of service and strength,” “Let America be America again,” “A new team, for a new America,” “Stronger at home, respected in the world,” “America deserves better,” “Let us make one America,” “Hope is on the way!” (weirdly prophetic), and “Help is on the way!” Not only does it look ridiculous every time you change your slogan, but you also have to change the placards and banners and all the other slogan-covered things and have them shipped to you. It costs, like, $10,000.

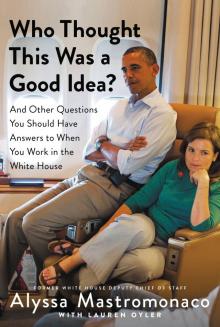

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?